San Diego Art Prize 2023

LARA BULLOCK Phd. Curator for the SD Art Prize 2023

…Mely Barragan’s work is about her experience as a Mexican living in the San Diego/

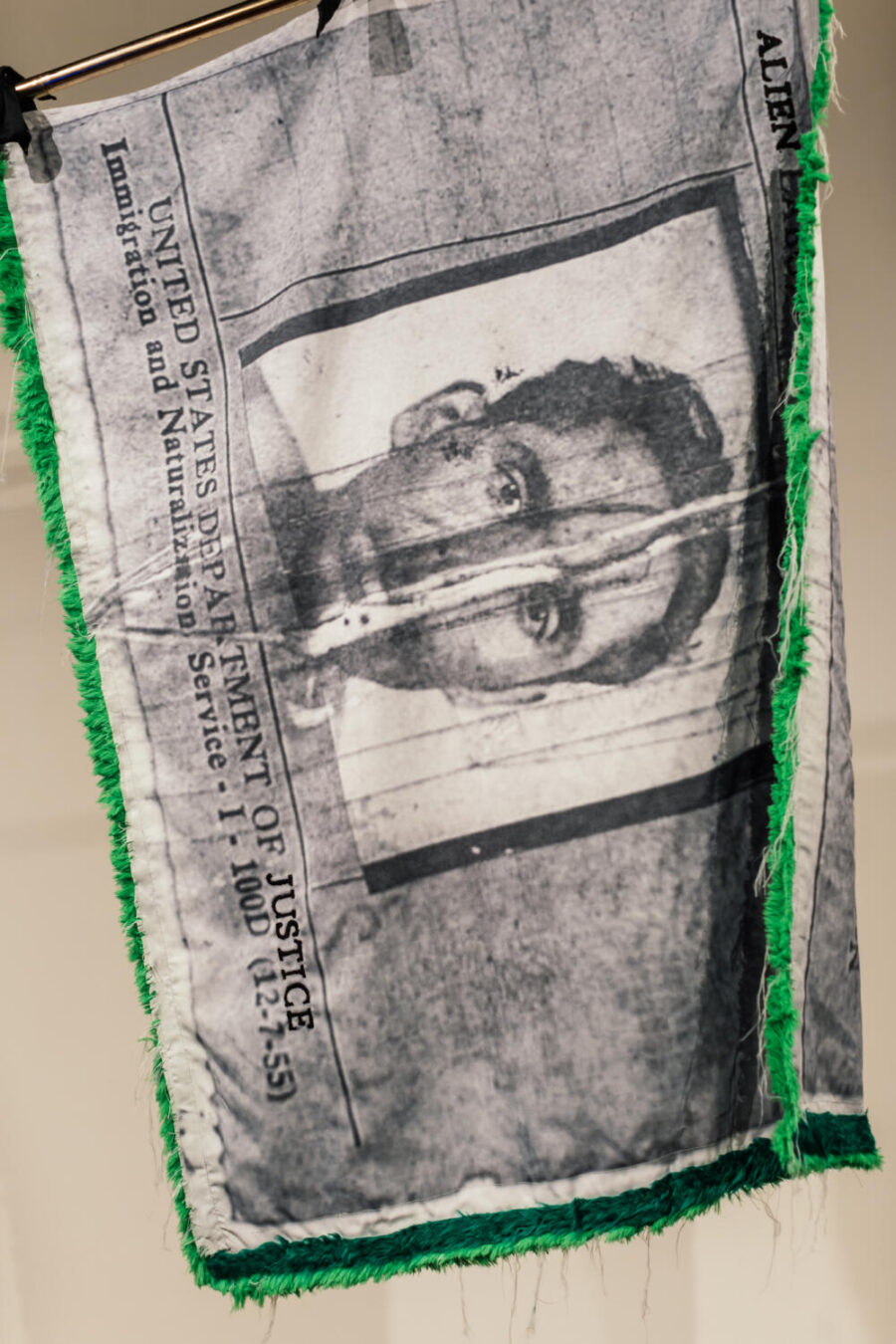

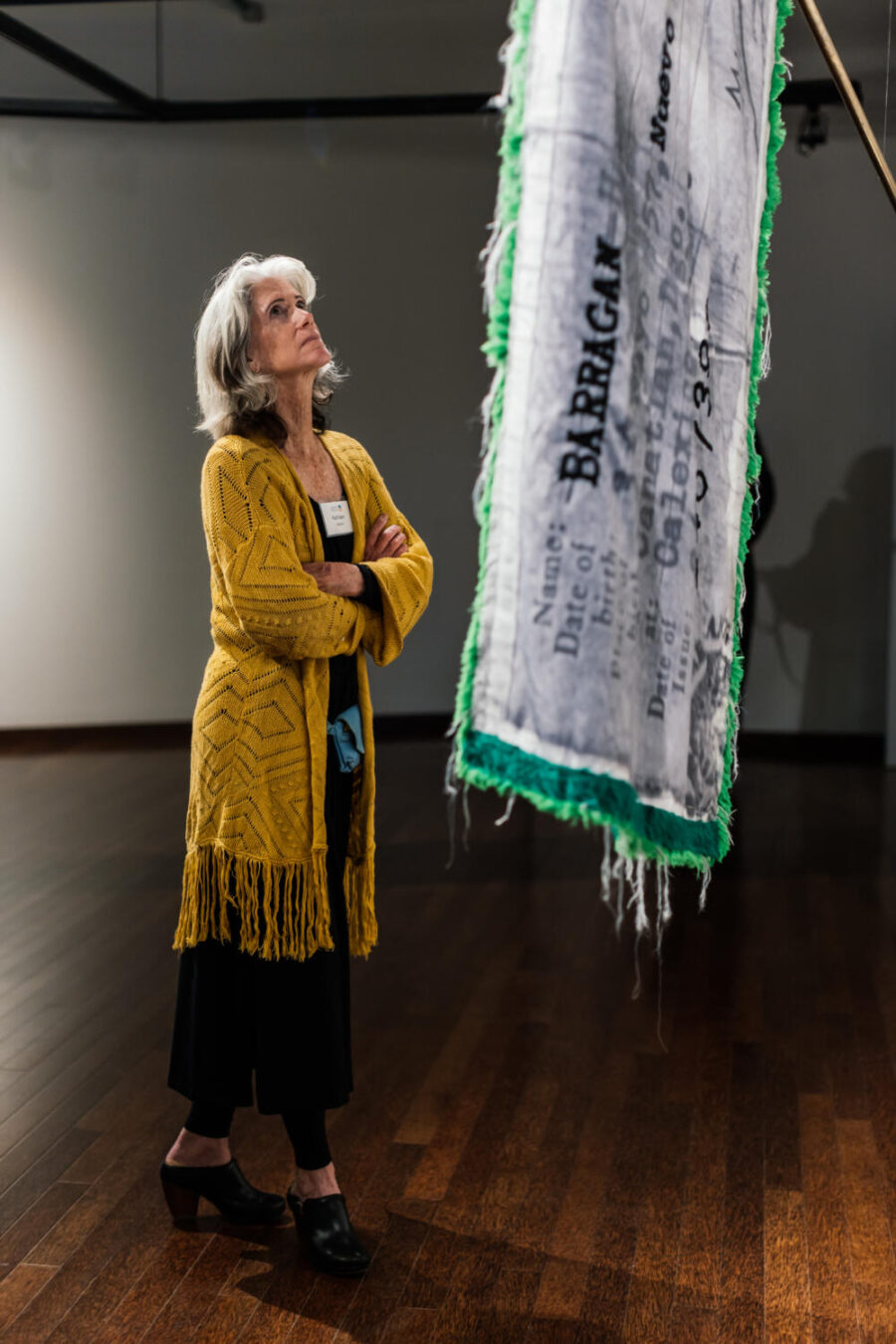

Tijuana cross-border region and its intricacies. Barragan’s objects are weighty. Shallow Water Emerges Til Dawn (2023) is a cascade of bodily, cloth appendages rushing down from ceiling onto the gallery floor. Hard, illuminated, bulbous, rocky sculptures, are interspersed amidst these appendages and seem like they could have come from Mars. Text in English can be discerned in some of them, a comment on how there is an expectation for Mexicans to speak English, but not for Americans to speak Spanish. These Post Human Accumulations provide a stark contrast to the softness of the tendrils. However, though it is tempting to focus on dialogical elements of the work, close looking complicates any sort of binary that one tries to construct. The tendrils that make up Shallow Water seem monochrome, but closer looking reveals they are in actuality a variegated collage of vinyl and fabric scraps from her grand-mother’s tablecloth, etc. Though they bear contracting qualities, in effect, the tendrils are as much accumulations as the Post Human Accumulations themselves; assemblage critiques of complexities of border-life and identity. Barragan’s Family Legacy (2023) speaks to her grandfather’s experience as a Bracero living in the border region. The softness of the flag which the artist stitched by hand, featuring his ID card portrait speaks to the blurriness between the delicate and the hard parts of life…

___________________________________________________

CHRIS KRAUS, Writer & Filmaker

Mely Barragan, San Diego Art Prize 2023

Born in the mid-1970s, Mely Barragan is part of a dynamic cohort of contemporary Mexican artists who began their careers in the Baja California border cities of Tijuana and Mexicali in the 1990s. At that time, there were no formal art schools in northern Mexico. They learned by looking to the work of their predecessors, and to each other. Nevertheless, equally influenced by international contemporary art, Mexican and history and border culture, they chose to remain. As Barragan told Frieze magazine in 2019, “The outside world didn’t know what to make of us. We were neither Chicano nor Mexican enough.” Since her first exhibition, Mi Gente, in 2002, Barragan has worked across media – from collage and painting to sculpture and installation – to explore and enact urgent ideas. Like the late American artists David Wojnarowciz and Dash Snow, Barragan is a total artist, responding to the experiences she’s witnessed and passed through. She begins by selecting materials she believes will best describe her ideas, although often she finds that the materials take on a life of their own. The physical and internal dialogue with materials manifested in the four recent works in this show has become increasingly complex and devious over the years. The collages and paintings created in the series Mi Gente (2002) depicted the imaginary characters Barragan invented as a small child. Her earliest memories involved a search for identity and a desire for justice. In Los Guerreros (2006) she assembled a series of metal sculptures from roadside muffler shops: human figures welded from mufflers as DIY signage by the owner-mechanics. At the time, international curators were trawling Tijuana in search of the new, so Barragan decided to create an installation that captured the visual reality of this border mecca’s cheap auto repair and medical care. She thought – Why don’t I bring all the mufflers together? She named each piece for the mechanic who made it. The work brilliantly depicted the chaos and warmth of urban life. But Barragan’s work isn’t always created in Tijuana. Since the early 2000’s, she has traveled to residencies from Russia to China, to Morocco and the American midwest. Such residencies are essential to any contemporary artist living outside an international center. Like the equally nomadic, New Zealand-born sculptor Kate Newby, Barragan has accepted and capitalized upon this enforced nomadic state. She travels light, carrying only ideas, using the materials she finds in these strange new environments to bring them to life. The sculptural works in this exhibition, all created in Barragan’s Tijuana studio during the past year, explore themes of personal and geopolitical history. Evading any easy description, they probe the undertow of psychic distress. In Family Legacy (2023), Barragan transforms her late grandfather’s old Bracero ID card into a magnificent banner or flag ringed by a fringe of chemical green. The ID card is a powerful totem, carrying both pride and shame. For twenty-two years, between 1942 and 1964, the Bracero program brought more than two million men to the US on short-term labor contracts and visas. The program defined a rich portion of Mexican cultural history that’s only recently begun to be rediscovered and claimed by projects like Ignacio Ornelas Rodriguez and Daniel Ruanova’s Bracero Legacy Project. To be a bracero was to become ‘one who swings his arms,’ working amidst toxic agricultural pesticides and hunched over all day with a short-handled hoe that ruins your back. The program also enabled her grandfather, Jose Barragan, to support his wife and twelve children in their home of Nuevo Ideal. “Among Mexican families,” Barragan recalls, “it’s a stigma to have been a bracero. It was so delicate and hard to talk about.” Over the years, Barragan came to realize that the Bracero program also helped to enforce a system of patriarchy, imposed upon families by historical circumstance and the culture itself. In Family Legacy, Barragan gently feminizes her grandfather’s experience, appropriating an heirloom that symbolized a man’s work and softening it with a granddaughter’s touch; sewing thread through the fabric that sustained her family. On the banner, Jose Barragan’s young face floats like a ghost. The card was issued to him by the US Department of Justice. By screen-printing the word ‘Justice’ in an almost imperceptibly bolder typeface, Barragan subtly, powerfully, evokes the unjust economic colonialism at the program’s heart. Shallow Water Emerges Til Dawn (2023), a stunning and monstrous assemblage, hangs from the gallery ceiling by hooks and aluminum chains. Shiny black latex tubes, given weight by embedded chain, cascade to the gallery flood in a menacing flood. The piece is one of the most ambiguous, troubling works by the artist to date. In it, Barragan alludes to a time of chronic illness when she was forced to inhabit a medicalized version of her own life. But the trauma conveyed by the work extends far beyond her own body. Shallow Water evokes a larger, shared illness: a literal toxicity that spreads across landscape, affecting all human relations. The black latex shimmers seductively, weighted by chains. Bodies, the work implies, have become wholly disposable, like medical waste. The work is a dream and a talisman for confronting fear. Installed alongside Shallow Water, Post Human Accumulations (2023) – four small- scale sculptures made out of electrical components, polyurethane foam, wood and glass – rest on the floor like small tumors. The sculptures are beautiful hazards, abstracting the biological waste and visual chaos across the US/Tijuana border into seductive and troubling form.

Discussion Closed